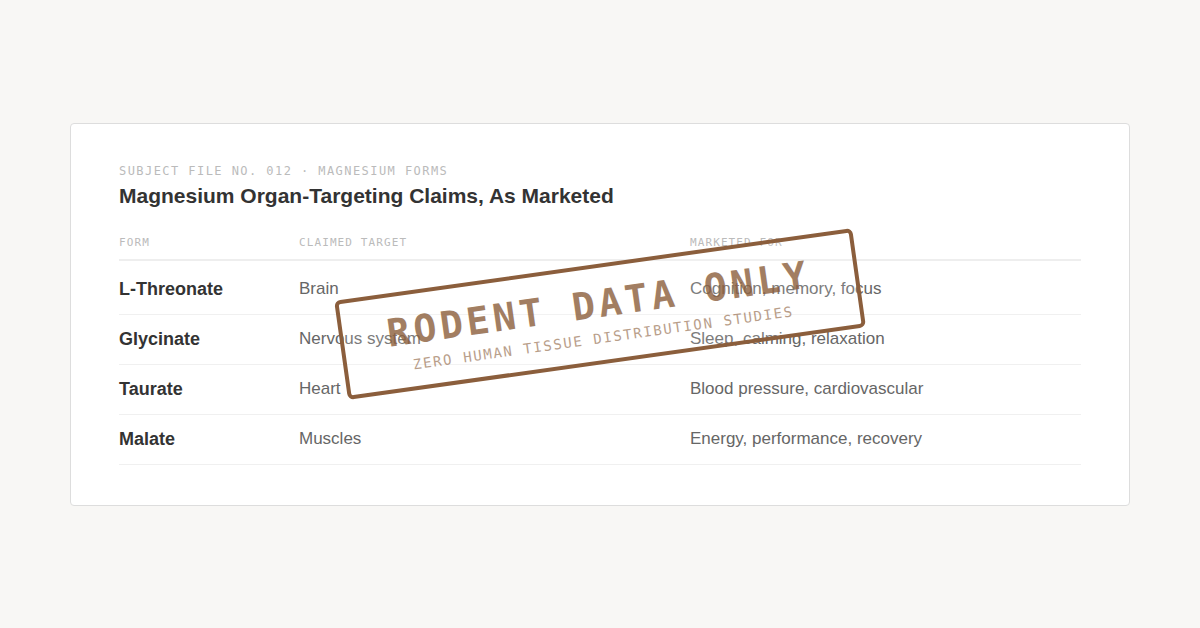

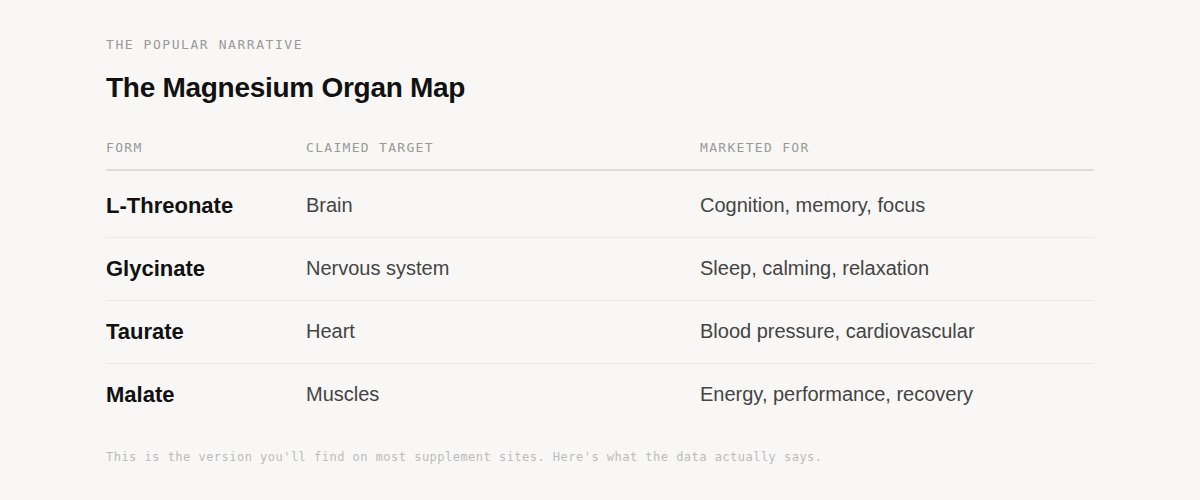

If you've spent any time looking into magnesium supplements, you've encountered the same claim repeated across brands, influencers, and Reddit threads: each magnesium form targets a specific organ. Threonate for brain. Glycinate for sleep. Taurate for heart. Malate for energy. It's clean, intuitive, and almost entirely unsupported by human data.

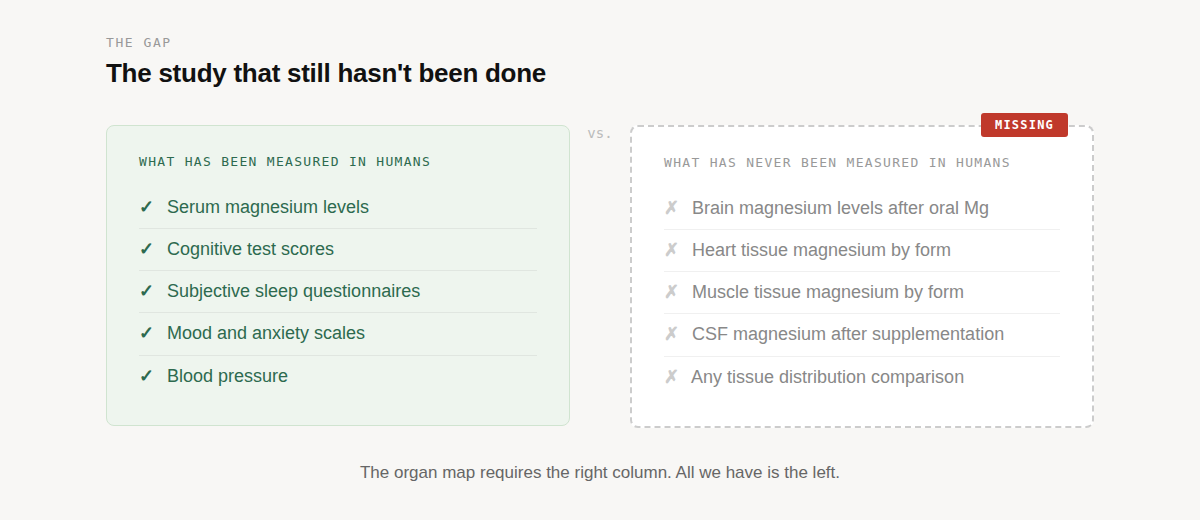

A 2021 systematic review¹ examined 14 studies comparing magnesium forms and confirmed what most people selling these products don't mention: tissue-specific distribution data exists only in animal models. No human study has ever measured whether any oral magnesium form preferentially elevates magnesium in the brain, the heart, or anywhere else over another form.

So where did the organ map come from? And if people are getting real results from specific forms, what are they actually responding to?

The Dissociation Problem

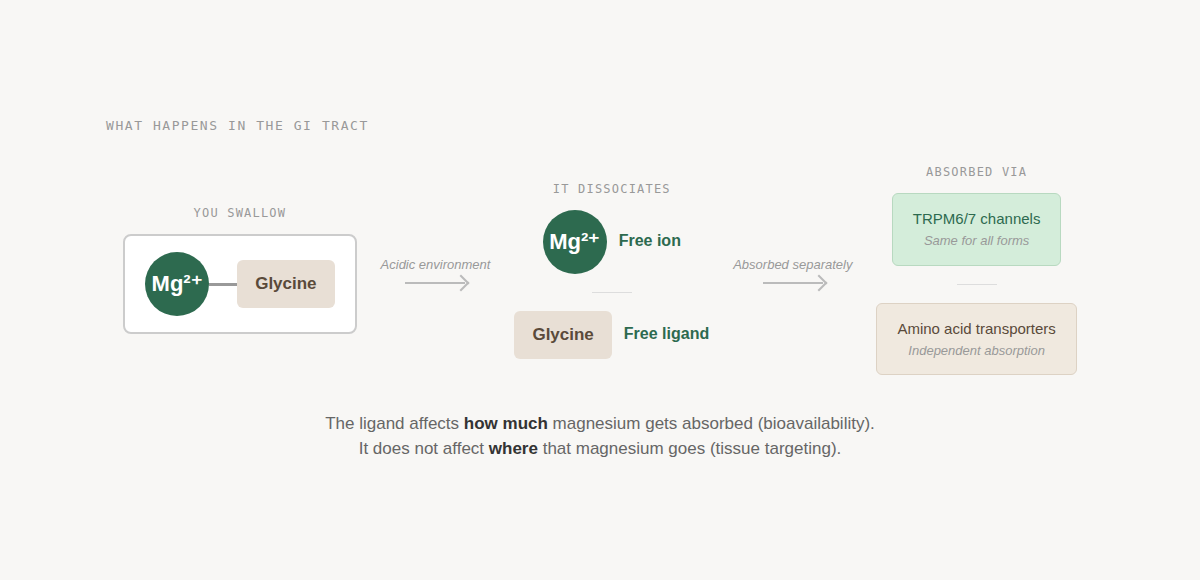

To understand why the organ map falls apart, you need to understand what happens when you swallow a magnesium supplement.

Every magnesium salt, whether it's threonate, glycinate, taurate, or malate, is a compound made of two parts: a magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) bonded to an organic molecule called a ligand (the glycine in magnesium glycinate, the threonate in magnesium threonate, and so on). When that compound hits the acidic environment of your GI tract, it dissociates (meaning that the ion and the ligand separate). The bond breaks. The magnesium goes one way. The ligand goes another.

This matters because once Mg²⁺ is free in the gut, it's absorbed through the same primary transport routes regardless of what it was attached to [passive transport between cells at higher doses, and magnesium channels (TRPM6/TRPM7) channels at lower doses].² There is a hypothesis that certain amino acid chelates like bisglycinate may be absorbed intact through peptide transporters (meaning the magnesium rides in on the amino acid's transport system without dissociating first), effectively bypassing normal magnesium absorption pathways. If true, that would represent a genuinely different mechanism. But the human evidence for intact chelate absorption remains limited and debated.³

What the ligand does clearly affect is how quickly dissociation happens and where in the GI tract it occurs, which influences how much total magnesium is available for absorption. That's bioavailability. But bioavailability is not the same thing as tissue targeting. A more bioavailable form puts more total Mg²⁺ into circulation. It doesn't route that magnesium to a specific organ.

This is the core distinction that the popular narrative skips entirely. When a brand says "this form targets the brain," they're conflating two very different claims: that their form delivers magnesium efficiently (which may be true) and that it delivers magnesium preferentially to one tissue over another (which has never been demonstrated in humans).

So, if the magnesium ion itself isn't being targeted, what's driving the form-specific effects people report?

Where the Claims Actually Come From

The idea that specific magnesium forms target specific tissues traces back to a small body of animal research and a recurring set of names. Before we go there, I will note that I am not against industry-funded studies. I have helped fund and been a part of several funded studies. What we should do is recognize the bias and desire to find positive outcomes that accompany that and consider the results in the context of the greater body of evidence on this topic.

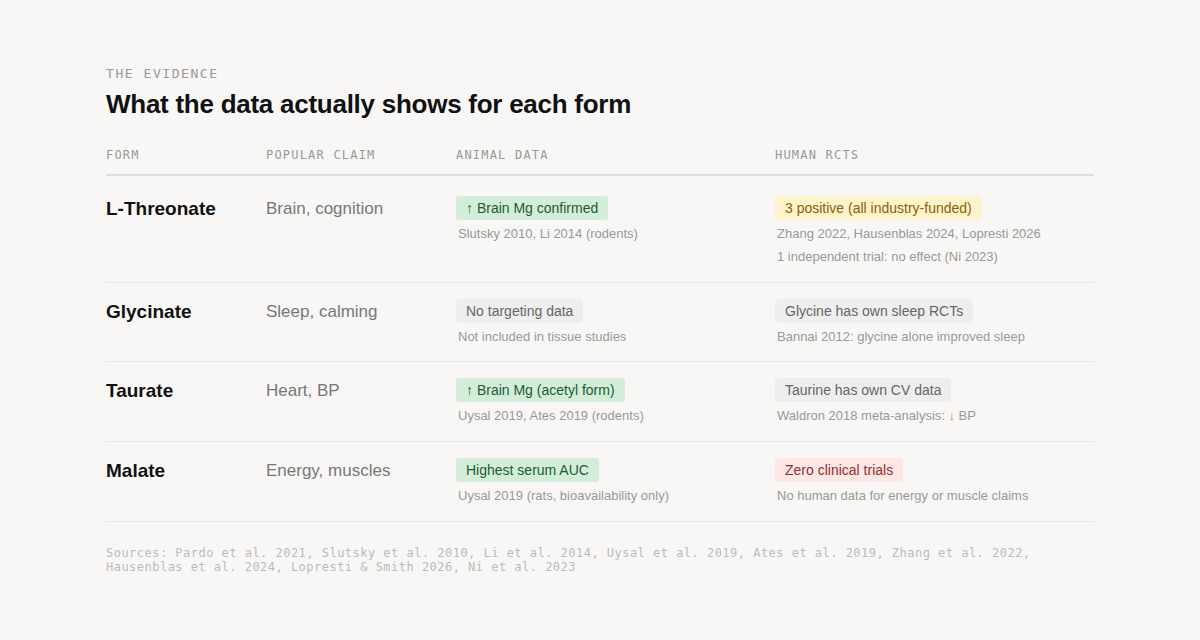

In 2010, Slutsky et al. published a landmark paper in Neuron showing that magnesium L-threonate enhanced learning and memory in young and aged rats by increasing synaptic density in the hippocampus.⁴ It was a compelling finding. It was also a rodent study. The lead researcher, Guosong Liu, went on to co-found the company that commercialized the compound (which is not unusual). Researchers patenting and commercializing their discoveries is a normal part of how science translates into products. The question isn't whether that happened, but whether the evidence base has grown beyond the original group.

Four years later, Li et al. (2014) used the same compound in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model and showed that magnesium L-threonate reduced amyloid plaque and prevented synapse loss.⁵ Another strong rodent finding, again with Liu as senior author. Together, these two papers form the foundation of the "threonate targets the brain" claim, both conducted in animals, both from the same research lineage.

The brain-targeting claim got a second line of support from a Turkish research group at Dokuz Eylul University. In two complementary studies, Uysal et al. (2019)⁶ and Ates et al. (2019)³ tested multiple magnesium forms in rats and mice (including acetyl taurate, citrate, malate, glycinate, oxide, and sulfate) and found that magnesium acetyl taurate achieved the highest brain tissue concentrations. Notably, neither study included threonate in the comparison. These remain the most comprehensive head-to-head comparisons of how different magnesium forms distribute across tissues, testing five to six forms each and measuring actual magnesium concentrations in brain, muscle, kidney, and heart tissue. Both were conducted in rodents.

No human study has done this. No human study has measured brain or cerebrospinal fluid magnesium levels after oral supplementation with any form. The Pardo et al. systematic review¹ confirmed it explicitly: tissue distribution data for magnesium forms exists only in animal models.

The Human Trials

What we do have in humans are cognitive and sleep outcome studies, and they deserve a closer look at who funded them.

Three industry-funded RCTs have reported positive results for magnesium L-threonate:

· Zhang et al. (2022)⁷: 109 healthy Chinese adults, 30 days. Improved memory scores. But the formula combined Magtein® (the patented form of magnesium L-threonate) with phosphatidylserine and vitamins C and D, making it impossible to attribute effects to magnesium L-threonate alone.

· Hausenblas et al. (2024)⁸: 80 adults with self-reported sleep problems, 21 days. Improved deep sleep scores and daytime functioning. Three of the six authors listed AIDP (the company that distributes Magtein®) as their affiliation.

· Lopresti & Smith (2026)⁹: 100 adults, 6 weeks. Improved cognitive scores and a 7.5-year reduction in estimated brain age. Funded by Threotech (the company that owns the Magtein® patent), conducted through a contract research organization.

All three measured outcomes like questionnaire scores and cognitive test performance. None measured brain magnesium levels. All three were funded by the company that owns or distributes the compound being tested (again, nothing inherently unusual about a company funding and publishing research to support product claims).

Then there's the outlier:

· Ni et al. (2023)¹⁰: 109 breast cancer surgery patients, 12 weeks. Measured pain, mood, sleep, and cognition. No significant improvement over placebo on any outcome. The only independent trial.

It's worth noting that this is not a clean comparison. The three positive trials enrolled healthy adults or people with self-reported sleep complaints. Ni et al. studied post-surgical cancer patients dealing with pain-related sleep and mood disturbances. That is a fundamentally different clinical picture. That difference in population makes it hard to draw direct conclusions either way. What it does tell us is that the only trial conducted without industry funding, in a population with arguably greater clinical need, found nothing (although it’s possible that “need” does not include magnesium of any kind).

What You Might Actually Be Responding To

If the magnesium ion is absorbed through the same pathways regardless of form, and no human data support tissue-specific targeting, then why do people report different effects from different forms? Glycinate users say it helps them sleep. Taurate users say it helps with blood pressure. These aren't imaginary responses. But the explanation might not have to do with magnesium alone.

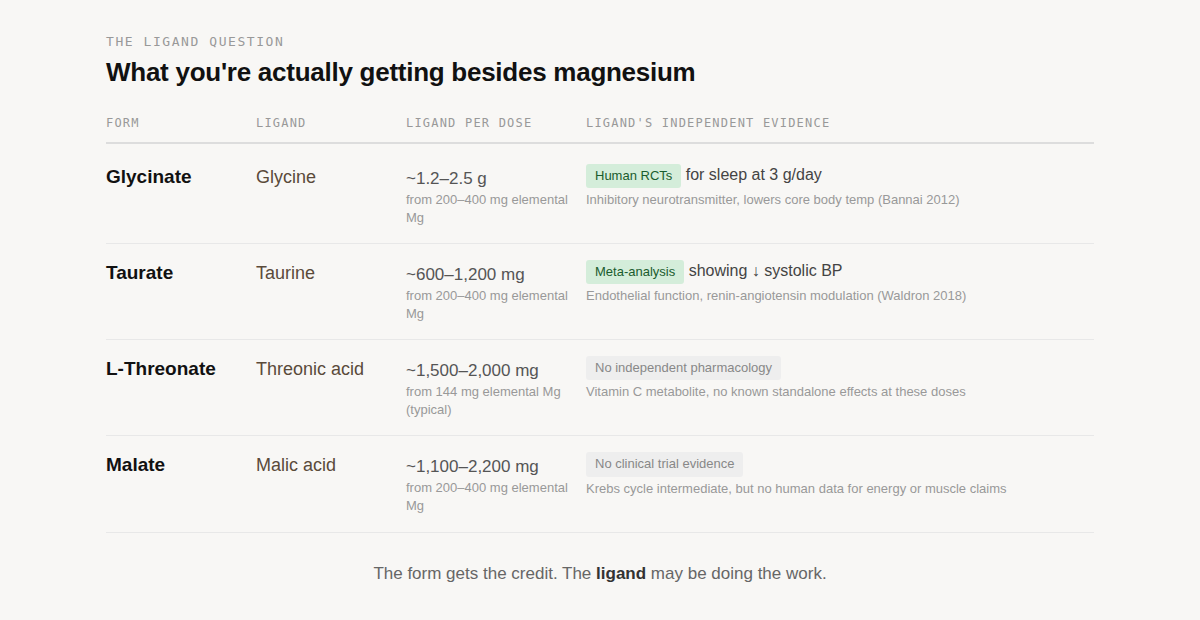

Remember that when a magnesium salt dissociates in the gut, both halves go their separate ways. The Mg²⁺ enters circulation through standard transport channels. But the ligand (the glycine, the taurine, the malic acid) also gets absorbed. And several (but not all) of these ligands have their own independent evidence base.

Glycine has been studied as a standalone sleep aid. At doses of 3g before bed, glycine has been shown to improve subjective sleep quality and reduce next-day fatigue in human trials, likely through its role as an inhibitory neurotransmitter and its effect on core body temperature regulation.¹¹ A typical supplement dose of 200-400mg elemental magnesium from bisglycinate delivers roughly 1.2-2.5g of glycine alongside it, which approaches the 3g dose used in standalone glycine sleep research.

Taurine has its own body of cardiovascular research. A 2018 meta-analysis found that taurine supplementation significantly reduced systolic blood pressure, with proposed mechanisms involving improved endothelial function and modulation of the renin-angiotensin system.¹² When someone takes magnesium taurate "for their heart," it’s possible the taurine alone may be doing meaningful work.

Threonate is the one case where the ligand story cuts the other direction. Threonate is a metabolite of vitamin C without a well-established independent pharmacology at supplemental doses. If MgT does have unique brain effects, the threonate itself is a less obvious explanation, which is partly why the animal data on brain penetration carries more weight for this form than for others.

Malate rounds out the picture. Malic acid is a Krebs cycle intermediate, which is where the "energy and muscles" marketing comes from. But oral malic acid supplementation has essentially zero clinical trial evidence for energy or muscle performance in humans. Malate did show the highest serum AUC in the Uysal rodent study⁶, meaning it kept circulating magnesium levels elevated the longest. That's a bioavailability finding (in rodents), not a targeting finding, and it has no human RCT data behind the specific claims being made.

This is the attribution problem at the center of the magnesium form debate. When someone takes magnesium glycinate and sleeps better, they credit the magnesium form. But they may be responding to the glycine. When someone takes magnesium taurate and sees lower blood pressure, they may be responding to the taurine (although magnesium itself has been shown to lower blood pressure in people with inadequate magnesium intake). The form gets the credit. The ligand may be doing the work.

What the Evidence Actually Supports

Magnesium supplementation works. That part is not in question. Nearly half of U.S. adults don't meet the estimated average requirement through diet alone, and correcting a deficiency (true deficiency, by the way, is rare) can improve sleep, muscle function, mood, and cardiovascular markers regardless of which form you use.¹ The problem isn't magnesium. The problem is the story being told about forms.

Here's what holds up: organic forms (glycinate, citrate, threonate, taurate, malate) are generally better absorbed than inorganic forms like oxide or sulfate.¹ If you're supplementing, choosing an organic form is reasonable. Magnesium L-threonate has the most research specifically behind its organ-targeting claim, including animal data showing genuine brain tissue penetration⁴,⁵ and three human RCTs showing cognitive and sleep benefits⁷,⁸,⁹ (though all three were industry-funded and none measured brain magnesium directly). Magnesium acetyl taurate showed the highest brain tissue levels in the only multi-form rodent comparisons we have (that, again, did not compare to magnesium L-threonate).³,⁶

Here's what doesn't: the organ map. The idea that you should take glycinate for sleep, taurate for heart, malate for energy, and threonate for brain (as though each form is a GPS-guided delivery system) has no human tissue distribution data behind it. The form-specific effects people experience may be real, but the mechanism might be the ligand doing independent work compared to the magnesium being routed to a specific destination.

If you're choosing a magnesium supplement, the most evidence-based approach is straightforward: pick a well-absorbed organic form, take it consistently, and understand that correcting any underlying deficiency is doing most of the heavy lifting. If you want to choose a form based on the ligand's independent effects – e.g., glycine for sleep, taurine for cardiovascular support, that's a defensible strategy. Just know you're making a ligand decision, not a magnesium targeting decision.

The organ map will probably keep circulating. It's simple, it's visual, it sells product. But until someone actually measures magnesium levels in human brain, heart, or muscle tissue after oral supplementation (the study that still hasn't been done), it remains a marketing framework built on rodent data and assumptions.

References

1. Pardo MR, Garicano Vilar E, San Mauro Martín I, Camina Martín MA. Bioavailability of magnesium food supplements: A systematic review. Nutrition. 2021;89:111294. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111294

2. de Baaij JHF, Hoenderop JGJ, Bindels RJM. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(1):1-46. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2014

3. Ates M, Kizildag S, Yuksel O, et al. Dose-dependent absorption profile of different magnesium compounds. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019;192(2):244-251. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01663-0

4. Slutsky I, Abumaria N, Wu LJ, et al. Enhancement of learning and memory by elevating brain magnesium. Neuron. 2010;65(2):165-177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.026

5. Li W, Yu J, Liu Y, et al. Elevation of brain magnesium prevents synaptic loss and reverses cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Mol Brain. 2014;7:65. doi: 10.1186/s13041-014-0065-y

6. Uysal N, Kizildag S, Yuce Z, et al. Timeline (bioavailability) of magnesium compounds in hours: which magnesium compound works best? Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019;187(1):128-136. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1351-9

7. Zhang C, Hu Q, Li S, et al. A Magtein®, magnesium L-threonate, -based formula improves brain cognitive functions in healthy Chinese adults. Nutrients. 2022;14(24):5235. doi: 10.3390/nu14245235

8. Hausenblas HA, Lynch T, Hooper S, et al. Magnesium-L-threonate improves sleep quality and daytime functioning in adults with self-reported sleep problems. Sleep Med X. 2024;8:100121. doi: 10.1016/j.sleepx.2024.100121

9. Lopresti AL, Smith SJ. Magnesium L-threonate (Magtein®) supplementation and cognitive function in adults: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Front Nutr. 2026. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1729164

10. Ni Y, Deng F, Yu S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the therapeutic effect of magnesium-L-threonate supplementation for persistent pain after breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2023;15:495-504. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S413435

11. Bannai M, Kawai N, Ono K, Nakahara K, Murakami N. The effects of glycine on subjective daytime performance in partially sleep-restricted healthy volunteers. Front Neurol. 2012;3:61. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00061

12. Waldron M, Patterson SD, Tallent J, Jeffries O. The effects of oral taurine on resting blood pressure in humans: a meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(9):81. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0881-z

Rosanoff A, Weaver CM, Rude RK. Suboptimal magnesium status in the United States: are the health consequences underestimated? Nutr Rev. 2012;70(3):153-164. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00465.x